Tsinghua University Breaks a 65-Year Limit: A Faster Alternative to Dijkstra’s Algorithm

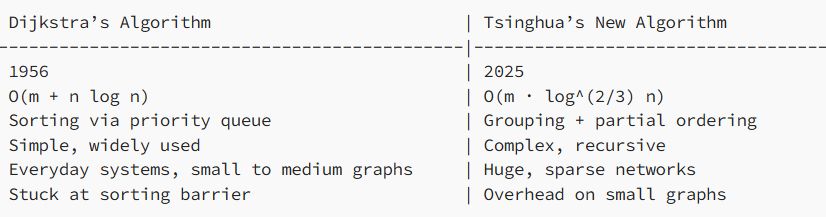

For nearly seven decades, Dijkstra’s algorithm has been synonymous with shortest-path computation. From textbooks to production systems, it has shaped how engineers and researchers think about graph traversal. By 2025, its dominance felt unquestionable—so much so that many believed the algorithm had reached a theoretical ceiling.

That belief was challenged when researchers at Tsinghua University demonstrated that the long-accepted “sorting barrier” in shortest-path algorithms is not fundamental after all. Their result marked the first asymptotic improvement over Dijkstra’s algorithm in general graphs since its introduction in 1956.

Why Shortest Paths Matter Everywhere

The single-source shortest path (SSSP) problem lies at the core of modern computing systems.

Whether routing packets across the internet, computing navigation paths in GPS systems, or enabling AI agents to traverse virtual environments, efficient shortest-path computation is essential. Dijkstra’s algorithm earned its reputation by being both elegant and reliable, making it a foundational component of computer science education and practice.

For decades, the prevailing assumption was simple: any correct and efficient solution to SSSP must pay a logarithmic cost for sorting. That assumption shaped generations of algorithm design.

Inside Dijkstra’s Algorithm: Where the Cost Comes From

Dijkstra’s algorithm works by expanding outward from a source node, repeatedly selecting the nearest unexplored vertex and relaxing its outgoing edges. This selection is typically implemented using a priority queue.

While this guarantees correctness, it introduces a performance cost. Each extraction and update involves sorting operations, leading to a time complexity of

O(m + n log n), where n is the number of nodes and m is the number of edges.

This logarithmic term became known as the sorting barrier, and for over 40 years it was widely believed to be unavoidable for general graphs.

Breaking the Barrier: A New Perspective from Tsinghua

In 2025, a research team led by Professor Duan Ran proposed a fundamentally different approach.

Instead of fully sorting all frontier nodes, the algorithm clusters nodes into groups and selectively explores representative elements. It combines:

- Bellman–Ford–style relaxations (which avoid sorting),

- Divide-and-conquer recursion,

- Strategic distance updates that reduce unnecessary ordering.

This hybrid design avoids full priority-queue sorting while preserving correctness.

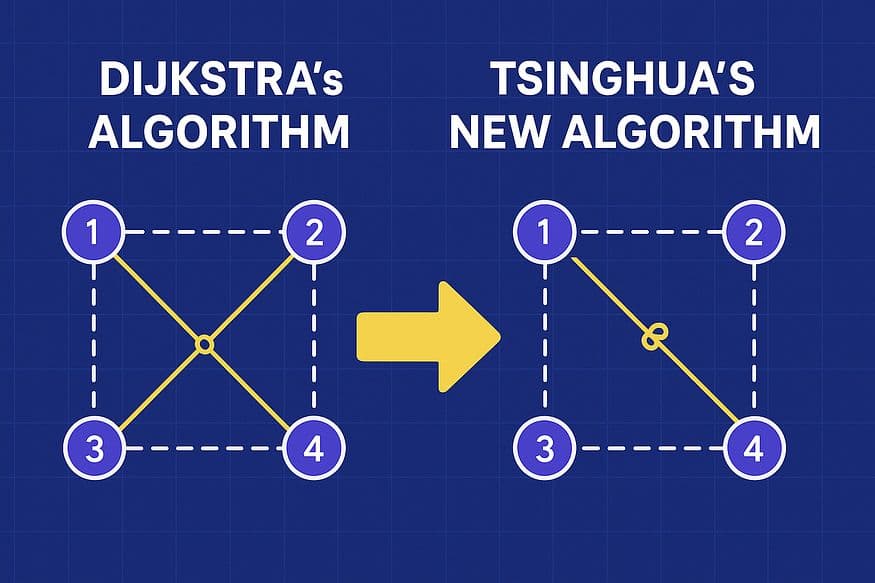

Figure 1: Comparison between traditional priority-queue-based exploration and clustered frontier selection.

Why the Result Matters (Even If It Looks Subtle)

The new algorithm achieves a theoretical runtime of

O(m · log^(2/3) n), which is asymptotically faster than Dijkstra’s algorithm for large graphs.

At first glance, the improvement may appear modest. However, from a theoretical standpoint, it is profound. It proves that the sorting barrier is not a law of nature—only a limitation of existing approaches.

For massive graphs used in data centers, large-scale simulations, and scientific computing, even small asymptotic improvements can translate into significant real-world gains.

The Trade-Off: Theory vs. Practice

Despite its breakthrough status, the new algorithm is not a drop-in replacement for Dijkstra’s algorithm.

- It is more complex and harder to implement.

- The overhead outweighs benefits on small or medium-sized graphs.

- In practical applications, heuristic-based methods like A* often remain faster.

As a result, Dijkstra’s algorithm is unlikely to disappear from navigation apps or production systems anytime soon.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Breakthrough Matters

The true importance of this result lies not in immediate deployment, but in what it represents.

By overturning a belief that stood unchallenged for more than six decades, the Tsinghua team has reopened foundational questions in graph algorithms. Their work invites researchers to explore hybrid and simplified variants that combine theoretical speedups with practical usability.

It also serves as a reminder that even the most trusted algorithms are not beyond improvement.

Conclusion: Progress Begins Where Assumptions End

Dijkstra’s algorithm remains one of the most brilliant ideas in computer science history. Yet this breakthrough demonstrates that longevity does not imply finality.

By breaking a 65-year-old limit, researchers have shown that progress often begins when long-standing assumptions are questioned. In doing so, they have opened a new chapter in algorithmic research—one driven by curiosity, persistence, and the courage to rethink what once seemed unchangeable.

References